CHAPTER FOUR Forms Most Beautiful and Most Wonderful (Part One)

There is grandeur in this view of life, with its several powers, having been originally breathed by the Creator into a few forms or into one; and that, whilst this planet has gone cycling on according to the fixed law of gravity, from so simple a beginning endless forms most beautiful and most wonderful have been, and are being, evolved.

-CHARLES DARWIN The Origin of Species, 1859

HANFORD’S ‘VERY EMINENT PLANT COLLECTOR William Lobb’, whom he felt important enough to quote in his letter to Joseph Hooker pleading for help in transporting the Discovery Tree to London, arrived in California in1849. Lobb’s mission was to make contact with travellers and plantsmen, acquire unusual seeds and living specimens, then pack and dispatch them on ships traveling via Cape Horn back to England. He was just forty when he landed in San Francisco, a veteran of a number of plant hunting trips to South America, and endorsed by his eminent employer James Veitch as ‘ready in resources, and practical in their application’.

Lobb was born at Lane End, Washaway, near Bodmin in Cornwall, in 1809. His father John was a carpenter at Pencarrow House built by Sir William Molesworth, the radical politician. When Lobb senior moved employment to Carclew House near Falmouth he encouraged William, the eldest of his three sons, and his brother Thomas also became a plant hunter, to apply for work in the gardens of the owner Sir Charles Lemon.

William did well and was encouraged to learn all there was about horticulture and botany. By the late 1830s his talent had been noticed and he was taken on by James Veitch whose father John had established a plant nursery twenty years before eighty miles away at Mount Radnour in Exeter. Veitch was an entrepreneur of prodigious energy who had set out his intention to become the purveyor of the best and most unusual plants to the aristocracy and moneyed of England, most particularly of London. By the 1840s James’s son, James Jr., had established a sister nursery in Chelsea near the banks of the Thames and on Jr.’s death in 1866 there was endowed ‘The Veitch Memorial Medal’ which, became a distinguished award of the Royal Horticultural Society of England for ‘persons of any nationality who have made an outstanding contribution to the advancement and improvement of the science and practice of horticulture’.

Before the advent of commercial horticulturalists, enthusiasm was dominated by ‘amateur’ British plant collectors who were motivated by deep-seated values of knowledge for the Glory of God, the furtherment of Britain and Empire, its celebration in art and literature, and collecting as a proxy for ownership of the natural world. But by the late 1700 and into the first half of the 1800s ‘Enterprise’ had become the religion of the newly wealthy merchant classes. The Empire was expanding and these parvenus wished to spend their money on philanthropy that flaunted their new social position. Town halls and libraries were endowed, huge houses built and lined with art acquired from Royal Academy exhibitions. Amongst the most status conscious, a garden containing exotic plants was de rigueur and myriad professional nurseries sprang up, happy to compete for their custom.

Veitch was by no means one of the biggest nurseries in the land. By the time of Queen Victoria’s accession in 1837 the Floral Calendar listed eleven seeds merchants and nineteen nursery men in London alone and one hundred and fifty across the British Isles. The most celebrated pioneering nurseryman of them all was Conrad Loddiges who established his Paradise Field Nursery in Hackney, London in 1777.

When Claudius Loudon published his Encyclopedia of Gardening in 1822 he laid down the principles of domestic gardening, creating a thriving market for new and exotic plants which he expanded upon with other bestsellers over the following fifteen years including his Encyclopedia of Plants and The Suburban Gardener. These books created such demand that by the late 1830s Paradise Fields covered 15 acres (6 hectares) with an inventory printed in a triple columned forty-eight pages catalogue, issued along side their very own illustrated monthly periodical the ‘Botanical Cabinet’.

Loddiges was a member of an ad hoc club of other like-minded nurserymen in Great Britain and the Continent who, when it suited them, shared plants and seeds so that nurseries were not spending huge sums duplicating each other’s expeditions. But by the mid 1850s Loddiges had over extended itself investing too heavily in hot houses and the engineering to heat them. Hackney had by then been absorbed into London making the land that much more valuable. Rent rocketed and so did their debt and they closed in 1855.

James Bateman was typical of the new and aspiring merchant class who wanted to mark his arrival with an ostentatious garden to absorb himself and impress his friends. He graduated from Magdalen College Oxford in 1829 where he ‘took a great interest in collecting and cultivating tropical plants’ particularly orchids a subject he became expert in. He joined his father who had made a fortune in iron, engineering and banking and in 1840 purchased Biddulph Grange in Congleton, Staffordshire.

With his friend the artist Edward Cooke he set about creating a garden, which to this day is, if not one of the greatest, certainly one of the more interesting in England. Bateman was a huge enthusiast becoming widely known for his talks on gardening and for his expertise. He spared no expense laying out a series of themed areas connected by avenues of the rarest and most sought after trees.

Persuading enterprising men to risks their lives and livelihoods travelling to exotic lands to find unique new commercially attractive plants was not a problem in this age of adventure. The problem was getting specimens back alive to be cultivated and then sold on at a commercial rate. Before the 1840s seeds were the currency of the Victorian plant collector, and tree and shrub seeds were relatively easy to transport because they remained viable if well packed. But getting live plants back from far-flung parts of the world remained fiendishly difficult. During long sea voyages they were by necessity confined to holds below deck and would almost certainly die from exposure to salt air, lack of light and little or no fresh water. But in1829 Dr. Nathaniel Bagshaw Ward a general medical practitioner living in Wellclose Square, East London stumbled on a solution that solved the problem and made a major contribution to the transformation of the British Empire, and thereafter the transportation of plants around the world by all nations.

A keen amateur naturalist, Nathaniel Ward was swept up in the Victorian fascination for growing ferns in his small townhouse garden. But no matter how many he planted and no matter how diligently he tended them his attempts ended in failure because of the terrible London air pollution. Day and night coal smoke billowed from domestic and manufacturers chimneys, coating every surface in thick black soot. Ward’s plants were stifled in the acrid air so he gave up and turned his attention to another Victorian gentleman's enthusiasm, entomology. In one experiment he tried to hatch a hawk moth caterpillar by trapping it in a sealed glass jar on some leaf mold. The moth did not emerge, but shoots of ferns and grasses appeared and thrived. Ward had by accident created the first self-sustaining terrarium. Ward’s jar remained closed for four years until the lid rusted allowing air to enter and the plants died.

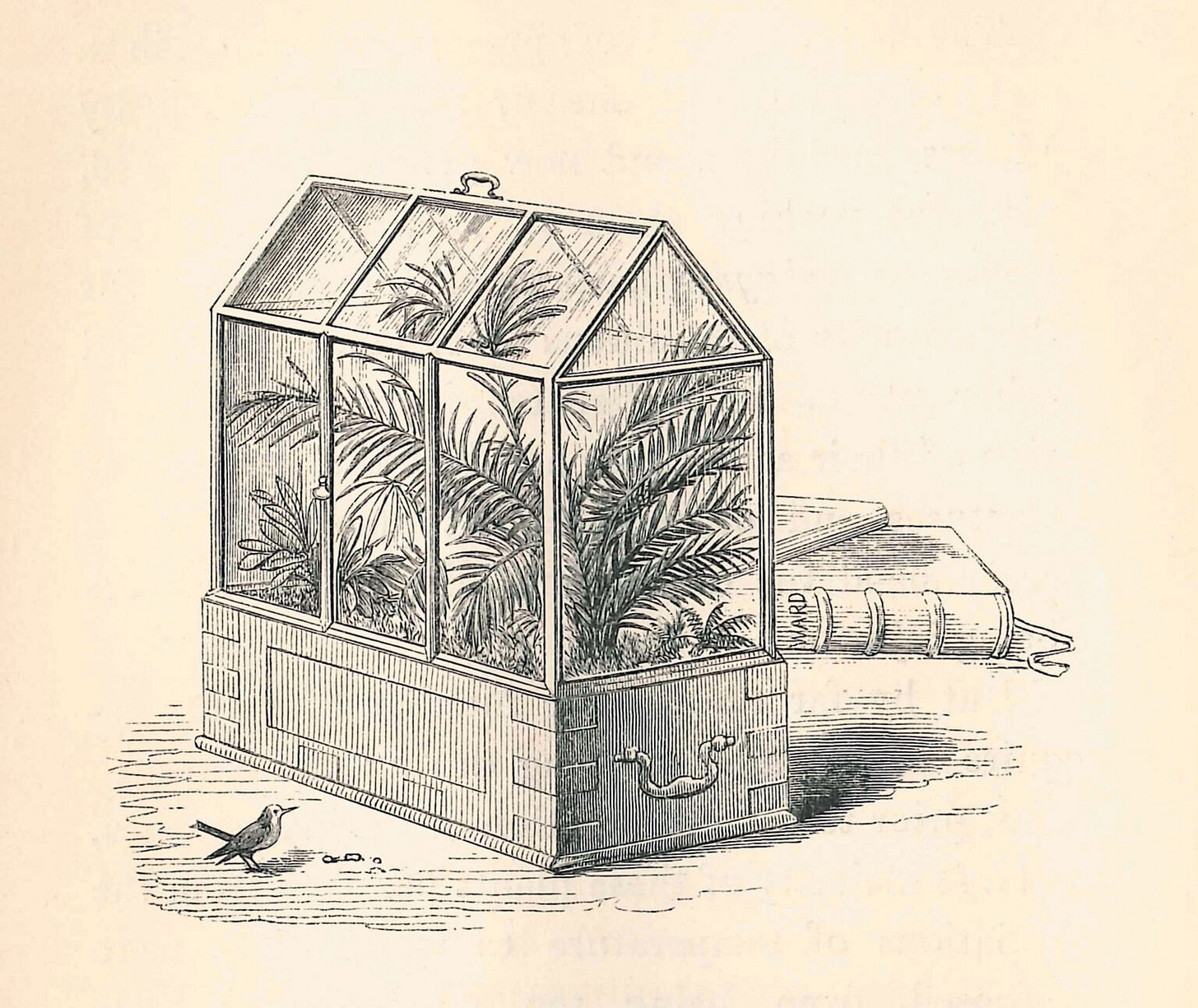

Ward’s illustration of one of his ‘Terrariums’ from his book On the Growth of Plants in Closely Glazed Cases, Nathanial Ward, 1852.

A Wardian case at the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. They were still in use well into the 20th century. (Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew).

Ward mentioned his discovery to his friend William Hooker the director of Kew Gardens who immediately thought that these sealed vessels might solve the problem transporting plants long distances. Hooker constructed some 'Wardian Cases' and took them on his exploratory expedition to Antarctica between 1839 and 1843, stopping off in New Zealand.

‘This morning I sent on board our large Ward’s case upwards of 4 foot long full of ferns and plants for Kew Gardens. I filled the bottom of the box with billets of wood, covered them with sandy soil and then put in the clay soil in which all these plants grow with some vegetable mold watered them until the water ran freely from the plug hole, let it drain covered it up and put on the covers’.

Some months later, the plants arrived safe and well in London.

This simple terrarium is one of the most important inventions of the Victorian era. Using Ward's cases Kew transported rubber plants from South America to the British colonies in Asia, as well as Cinchona plants, from which quinine is derived, to India. But without doubt their greatest early use was by Robert Fortune on his voyage to China on behalf of the Horticultural Society in February 1843. Using ‘Ward Cases’, he ‘stole’ 23,892 young tea plants and approximately 17,000 germinated tea seedlings from China and transported to Assam and Sikkim in the foothills of the Himalayas completely changing how tea was grown, drunk and transported.

Veitch’s nursery was certainly known to have their plant collectors use Ward’s cases. Richard Pearce who worked for Veitch a few years after Lobb in the late 1850s in South America, sent back a plethora of plants in ‘large Wardian cases’, but it is not recorded definitively that Lobb used them to transport his living samples back to London.

NEXT WEEK: THE GREAT GIANT SEQUOIA SEED RACE.

Having collected as many cones, pieces of bark, wood samples and saplings as he could carry, Lobb returned immediately to San Francisco, arriving just in time for the next fortnightly steamer day, when ships left for Panama. Lobb plainly knew the significance of what he had and was intent on being the first to bring this wonder of the world back to London.